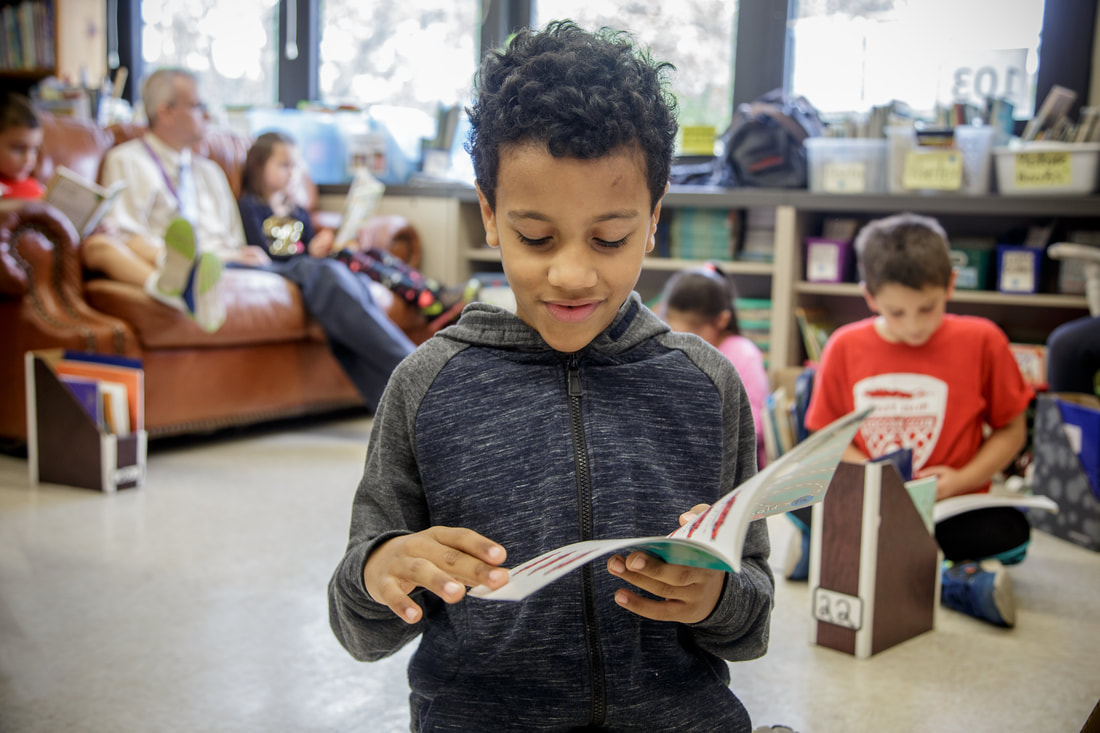

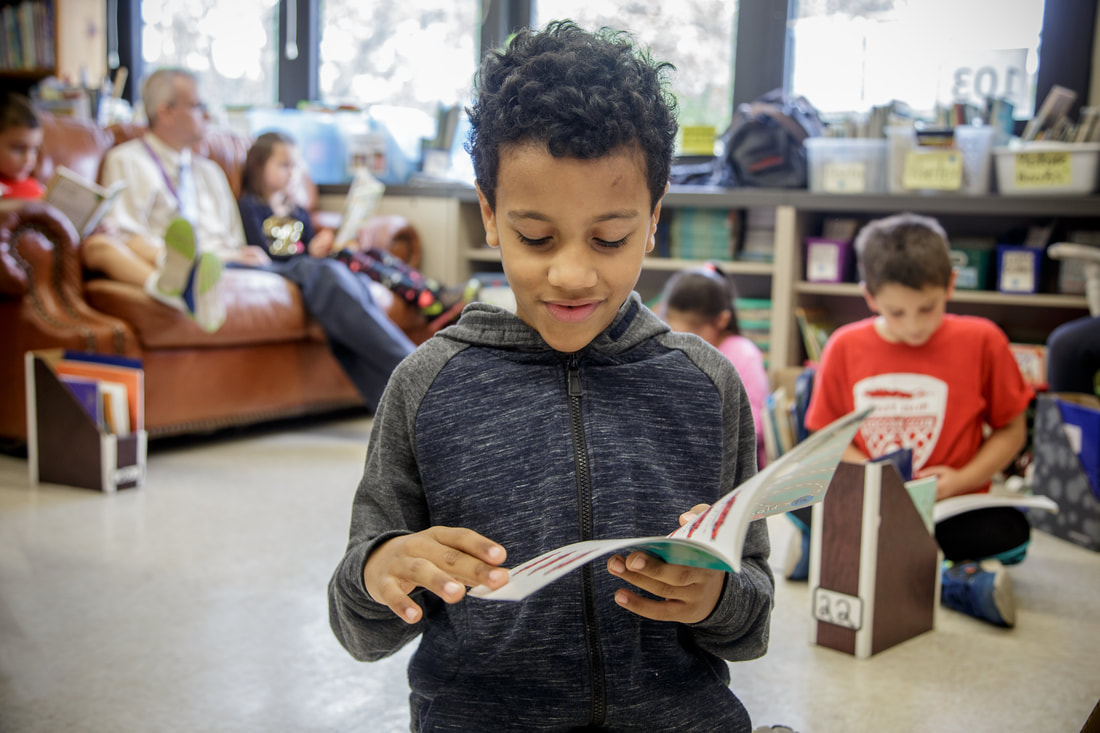

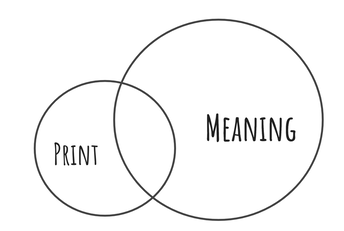

As educators, our ultimate goal, of course, is for readers to be equally proficient in navigating the print and in comprehending what they read. In fact, the more we understand about how individual children are doing these two things, the better we can teach them. So the reading process of a proficient reader can be generally represented like this:

I first represented the print/meaning duality with with this two-circle Venn Diagram when I was a regional language arts consultant in 1999, because I wanted all of the work I did with teachers anchored in understandings of children's reading processes. Literally every workshop I've ever taught across two decades, has been held up by this mental model.

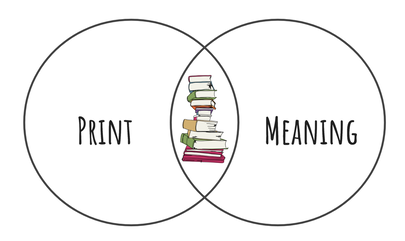

Of course, not all children are equally proficient in both print and meaning, and variations on the Venn diagram can illustrate some of the differences. For example, children who are skilled in decoding but don't comprehend well, are represented with the same two circles, but the meaning circle is smaller. This reduction indicates that the stronger proficiency is in the area of decoding/word recognition, like this:

Children with "small meaning circles" have difficulty with language comprehension. Their spoken vocabulary, general knowledge, and/or facility with language structure are typically limited, which places a ceiling on their reading comprehension. Children who's reading looks like this may rely on context to figure out words with little or no attention to the letters on the page.

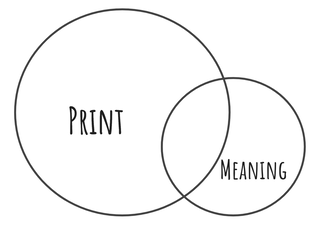

Similarly, children who are not skilled with reading the words (vs. understanding the words), are represented with the opposite pair of asymmetrical circles:

Children with "small print circles" have limited orthographic knowledge. They don't fully understand how our alphabetic code works. Consequently, if tricky words are not sufficiently supported by context (which happens increasingly as text gets more difficulty) they get really stuck.

You can read about this simplified model in Preventing Misguided Reading (Burkins and Croft, 2010), Reading Wellness (Burkins and Yaris 2014), and Who's Doing the Work? (Burkins and Yaris, 2016).

There are a number of factors that contribute to children reading in ways that favor meaning or favor print, paying insufficient attention to the other source of information. The most troublesome cause, however, is us, their teachers. If our instruction is biased towards print or meaning, then it is possible for children to learn to rely on that source of information and neglect the other. This is, or course, unintentional.

In the next post in this two-part series, I will describe one of the ways we can inadvertently teach children not to use the print or not to comprehend.

Who's Doing the Work? (Burkins & Yaris, 2016) explores the ways we support students in problem-solving, especially if they are grappling with something that is really requiring them to think deeply and work hard. Right now, when so much about our instruction is different than usual, asking good questions is a reliable and familiar friend.

Of course, we all know that asking higher-order questions can help children learn more. But, while asking "good" questions remains important in mask-to-mask and digital spaces, it's what we do after we ask the question that matters next.

I recently encountered, however, a bit of research on math instruction that is making me think about the limits of these "good" questions.

In a study that compared the way math teachers ask questions during math instruction , researchers found that only 1 in 5 questions required children to make deep connections across the content. This does not seem like big news; we are all aware of the need to ask more questions that push children to take the content they are learning to levels of analysis and connection. We also appreciate the important role that procedural questions ("low level") play when learning new information or processes. Certainly, it would be silly to try and make every question higher- order.

What is most fascinating about the study mentioned in Range, however, is that in many cases, when better questions were asked, children still didn't get the opportunity to think deeply about the content. Rather than actually getting to do the work, they were given a series of "hints." So even though the work began with an invitation into deep thinking, their thinking was actually hampered during the process of answering the question.

While 1/5 of questions in the study were high-level questions, requiring students to deeply process the content, students received hint after hint in the form of a low-level question. So, low-level, hint-giving questions, eliminated the value of the original, good question.

Historically, in developing better questions for reading instruction, we put a lot of energy into thinking about levels of inquiry and Blooms Taxonomy. We craft the questions thoughtfully, but the moments after the initial question matter just as much as the question. In fact, with hint-giving through a series of low-level questions, a question such as, How do authors show the ways characters change over time? becomes no more thought-provoking or learning-inducing than a question like, Who is the main character?

Fortunately, there is a magic bullet for letting our better questions do the work we intend for them to do. The simple practice for making the most of our good questions it to, quite simply, wait.

Wait time is the critical complement to a good question, and it is proving even more tricky in virtual instruction. A few seconds can feel like forever when you are up close on a camera screen. Instructional time is somehow different in this new time-space-continuum. But just because it feels like forever, doesn't mean it actually is forever. In virtual instruction especially, and in light of the negative effects of "hint" giving to move things along, just giving students time to think remains essential.

Now more than ever, the way we support students in answering questions is just as important as the question itself.